News

Judge Rules Against Theo Harper ’25 in Harvard IRC Lawsuit Following Removal Over ‘Stress Test’

News

‘Deal with the Devil’: Harvard Medical School Faculty Grapple with Increased Industry Research Funding

News

As Dean Long’s Departure Looms, Harvard President Garber To Appoint Interim HGSE Dean

News

Harvard Students Rally in Solidarity with Pro-Palestine MIT Encampment Amid National Campus Turmoil

News

Attorneys Present Closing Arguments in Wrongful Death Trial Against CAMHS Employee

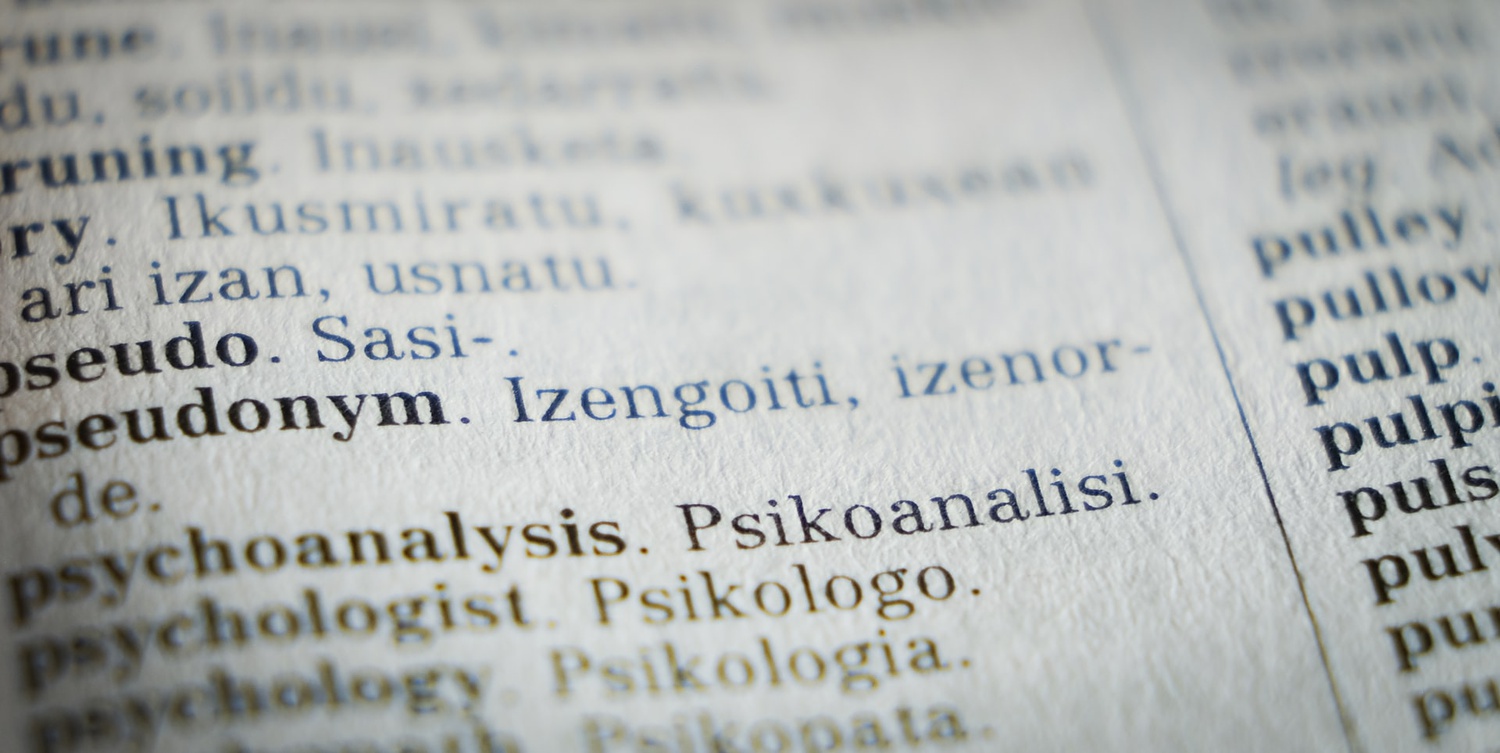

The Words We Lose: The Merits and Disadvantages of Reading Translated Literature

Translating a text from one language to another is doubtless a difficult undertaking for myriad reasons, but the reality of an untranslatable word or phrase presents perhaps the most thought-provoking dilemma for translators and linguists everywhere. Naturally, the central discourse concerning translated works regards textual fidelity. What should a translator prioritize in their work to make it most faithful to the original text? Meticulously preserving its word-for-word accuracy, or its connotational precision?

There is something intrinsically lost in translation in either case. If the words you are reading were not originally written in English, you have likely missed some parts of the original text through no fault of your own, nor of the translator’s. It is for this reason that we must be conscious of the translated books on our syllabi and bookshelves alike as slight distortions of their original works rather than as exact copies of them.

Without an English equivalent, even small, common phrases can rear large philosophical problems without clear answers for translators. While the French phrase “c’est la vie” literally means “this is the life,” a translation of “that’s life,” or even “it is what it is” in English might well serve as better translations of the same phrase given how it’s used in francophone countries. This distinction is often called that of connotation and denotation. A similar problem exists with words that seem to have obvious definitions across many different tongues too. One of the most beautiful facets of translation is that from a single text, many new interpretations, however slightly dissimilar, can arise.

The word “llegar” in Spanish could mean either to come, to arrive, or to reach one’s destination in English. Were two separate translators to approach this word, they would have a tough choice laid out before them in synonyms. Indeed, almost every word has a useful synonym within reach, and the very concept of a synonym implies an inherent, though slight, contrast between two or more words. Yet no matter how small the difference between these synonyms, our hypothetical translators would have each created a distinct text through their word choice. Despite their small size, the disparities between “to come” and “to arrive” can matter a great deal in the context of a 200-page work.

In Attic Greek, there are at least six different words for love, all connoting different meanings. The word “philia,” for instance, is translated in the “Liddell & Scott Greek-English Lexicon” as “friendly love” or “affection.” The word “agape” is given the similar though still distinct definition of “brotherly love” within the same text. In English, the word love — or friendship, were the author to choose the more granular option — would most likely be used to describe either of these phenomena, despite their differences. Through Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott’s translations of Classical Greek texts, it is especially clear that we miss certain characteristics of these concepts if we attempt to translate them using our closest single-word equivalents. Instead, adjectives must modify love, a near catch-all term for affection in the English language, to begin to describe the complex categories of this ideal detailed many centuries ago by the Ancient Greeks. What results is often a clunky and still inadequate substitute for the original term as deployed by such authors as Plato and Aristotle.

In an interview with “The New York Times,” Emily Wilson commented on the first line of her own translation of Homer’s “Odyssey.” She translates the Greek text as, “Tell me about a complicated man.” In the interview, however, Wilson said that she could have written instead, “Tell me about a straying husband,” due to certain other definitions contained within the connotations of a critical word in the sentence. Though within certain contexts, this is certainly a valid translation, Wilson herself admits the differences between the two sentences are vast. If each translation is easily justifiable, how can the reader know what the text’s first line truly connoted?

Many courses at Harvard use translated literature as central texts. By no means do I advocate for the omission of these texts from our syllabi; the act of translation is incredibly important to the democratization of literature and the arts at large. I do, however, hope that we can be mindful that many of the works we read in courses on world literature such as Humanities 10 — where I first encountered Wilson’s version of the “Odyssey” — are translated. When performing a close reading on such a text, we must recognize that the intent of the author and the intent of the translator may not align perfectly. The words Stuart Gilbert uses to capture those of Albert Camus in “The Stranger,” for example, are naturally colored by his interpretation of the work. His use of one English word as opposed to its synonym is almost certainly informed by his sense of the work’s meaning. And much like the relationship between a word and its synonym, no matter how close Gilbert’s understanding of “The Stranger” is to its author’s, he will not accurately capture everything Camus tried to convey through his own words in an English translation.

Recently, classical translation has become a particularly fashionable mode of writing due to the novelty any given translator can give to ancient words written by Homer, Horace, Sappho, or Sophocles. While some of Anne Carson’s translations in “If Not, Winter” may be more Carson than Sappho, it’s easy to admire Carson’s attempt to connect a new audience with ancient poetry. Additionally, attempting to translate Sappho’s poetry myself alongside Carson constituted some of the most fun and fulfilling extracurricular work I myself have completed all semester.

In many ways, the translation of a text is futile. No author’s words can be captured entirely honestly in a language other than that in which they were written. Certainly not in both their connotation and denotation. Yet the act of translation is beautiful. It is kind. It stretches across insurmountable divides and helps form a well-needed global community of readers. Fundamentally, a translator has read something that they found interesting and has decided to share it with a broader audience. To say, “Look. See how I loved this. I want you to love it too. Let me give it to you,” — What could be more human? Reading in translation is one of the most important ways we can connect with a broader, more diverse selection of readings than those with which we’ve grown up. If we recognize the inherent deficiencies of these translated texts on levels of both connotative and denotative accuracy, the consumption of translated texts can be a gorgeous cross-cultural exchange of knowledge that emphasizes both the differences and commonalities that fall across humanity.

—Staff writer Eleanor M. Powell can be reached at ellie.powell@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.