News

HUPD Says No Active Threat After Cambridge Police Officers Pursued Suspect Through Harvard Yard

News

‘A Real Loss’: Starlight Square to Shut Down After Four Years of Bringing Cantabridgians Together

News

Jeremy Weinstein Was Offered the Harvard Kennedy School Deanship. Who Is He?

News

Interim Harvard President Alan Garber’s 100 Days of Trial By Fire

News

‘An International Issue’: Harvard GSAS Dean Says Free Speech Issues Are Not Harvard-Specific

What Happened to Changing the World?

I can remember the night I decided to come to Harvard. My other choice was Carleton College, off in the cold woods of Minnesota, a spectacular environment not unlike the one where I’ve since spent most of my life. Harvard was too close to home, a 15-minute bus ride from Lexington where I’d grown up. I was leaning against, opting for adventure.

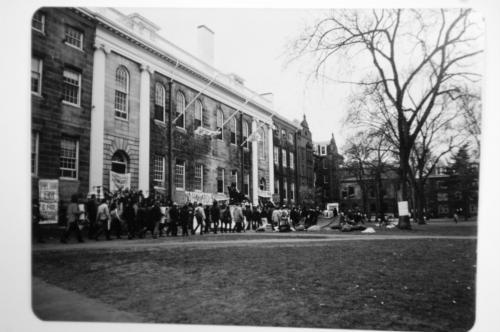

And then that April evening in the spring of 1978, I came in to take a look. There was a demonstration going on against apartheid and for divestiture, words that didn’t mean all that much to me. But there was a mile long line of people snaking through the campus: “Out of The Dorms And Into The Streets,” “Hey Hey Ho Ho, Apartheid Stock Has Got to Go.” And at The Crimson, kids were dashing in and out, notebooks and cameras at the ready. The protest had been organized in a day, after that morning’s edition had broken the news that the Harvard Corporation was planning to hold on to its shares in banks linked to South Africa, news that an intrepid reporter had gotten by climbing into the dumpster outside the University printing plant out past the football stadium.

It was simply too much fun to miss—I sent in my acceptance the next morning.

As it happened, that was the largest single demonstration during my time at Harvard—nothing in our four years quite matched it. But I watched the anti-apartheid movement soldier on, sitting mostly on the sidelines as befits a newspaper reporter. And I watched in the years that followed, when the hero of that movement, Nelson Mandela, in fact turned out to be one of the few great giants of the twentieth century. (It’s still embarrassing to remember that the wise men of the College, President Derek C. Bok chief among them, placed their bets instead on the avaricious tribal leader Mangosothu Buthelezi.) When Mandela was finally freed, one of his first trips abroad was to visit the American universities to thank those who had worked for divestiture. I’m not given to much sentimentality about the best-years-of-our-lives-etc., but it did make me proud to think that some small echo of our noisy battles in Cambridge had been heard in the jail cells on Robben Island.

In any event, fast forward a quarter century. Having spent most of my time since graduation working on global warming, I found myself last summer in a funk. The nation was finally beginning to accept the reality of climate change—Hurricane Katrina had blown open the door, and Al Gore ’69 had walked through it with his fine movie. But still there was nothing happening in Washington—the 20-year bipartisan effort to accomplish absolutely nothing about the greatest problem humans have ever faced continued unabated.

And so it seemed time, to me, to go beyond just writing and speaking about global warming, and to try my hand at a little organizing. First we put together a march across the state of Vermont, where I live. It was wildly successful—but it was Vermont. So we decided to try going national. (“We” in this case means me and six kids who had graduated from Middlebury College in the last six months.) We set up a website, stepitup07.org, and in early January sent out an appeal asking people to organize rallies for April 14. Our secret hope? That we’d coordinate a hundred such events.

Instead, though we had no money and no organization, we found so many eager people that we managed to pull off 1,400 rallies in all 50 states on that Saturday in April. And they were just as cool as that long-ago march through Harvard Square: We had scuba divers holding underwater demonstrations off the coral reefs of Key West and skiers descending in formation down the dwindling glaciers of the Rockies; we had crowds of people in blue thronging lower Manhattan to form a “sea of people” to show where the new tideline would someday fall; we even had a crane winching a yacht twenty feet into the air above Jacksonville Florida to show the new sea level if Greenland slides into the ocean.

Along with lots of other events of the spring, including new scientific reports and a landmark Supreme Court ruling, it had its effect: All of the leading Democratic presidential contenders have now endorsed our call for 80 percent cuts in carbon emissions by 2050. We’ve moved the bar a little.

And it reminded me again how important protest is. Institutions like Harvard, and the eminently rational and mainstream people who run them, help rule the world. But they are bent sometimes by the moral force that bubbles up when other people have had enough with things as they are, and wish for something better (as this spring, when Harvard students went on hunger strike to raise the pay of security guards). You’re supposed to come to college and be a radical and then go off and grow up. Some of that is unavoidable and necessary.

But as we head into the later parts of our lives, it’s worth remembering that some of the noblest teachers we had here were those people rattling on and on about apartheid. People who were not necessarily ruling the world, but changing it. Which is even better.

William E. McKibben ’82 was president of The Harvard Crimson in 1981. He is the author of ten books, most recently “Deep Economy,” and a scholar in residence at Middlebury College.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.